the state I am in: Curated by Elisa R. Linn and Lennart Wolff

-

Overview

With works by James Gregory Atkinson, Noah Barker, Nicolas Ceccaldi, Peter Fend, Lea Grundig, Jacqueline de Jong, Laura Langer, Louise Lawler, Oswald Oberhuber, Li Ran, Lotty Rosenfeld, Bruno Serralongue, Bri Williams and Leyla Yenirce

Capitain Petzel is pleased to announce the group exhibition the state I am in, curated by Elisa R. Linn and Lennart Wolff.

In the gallery's modernist pavilion located on the former monumental marching corridor of the GDR, the exhibition brings together fourteen artists and addresses the contradictory relationship between nation, state, and art. The artworks in the exhibition span not only from the post-war era to the present but also the variety of state systems: capitalist, socialist, democratic, authoritarian, and fascist.

A state is both an order and a condition. It is the social mediation of various conditions and the struggle for representation – recognition and rights – within that order that is conceived as politics. Art is implicated in this struggle for recognition and rights as it waged over the image of society. Here the nation-state provides the dominant frame which itself can be understood as constructed around a fiction: the congruence of the nation, people, and state borders.

Historically, art's role in the construction of an image of the people was central to the birth of modernism and the emergence of different forms of nationalism, for instance, civic or ethnic. When appearing to be made by the people themselves, the images would situate an aesthetic judgment, producing an experience where the people recognized itself as autonomous and sovereign. This recognition emboldened a promise of universal and liberal values – freedom, individual rights, and rule of law – that the modern nation-state never delivered, as the over-represented oppressed those barred from sovereignty along racial borders.

Amidst what is widely perceived as a decisive rupture in the post–Cold War order, the exhibition brings together artistic practices that demarcate shifts in representation at the critical juncture of the nation-state today.

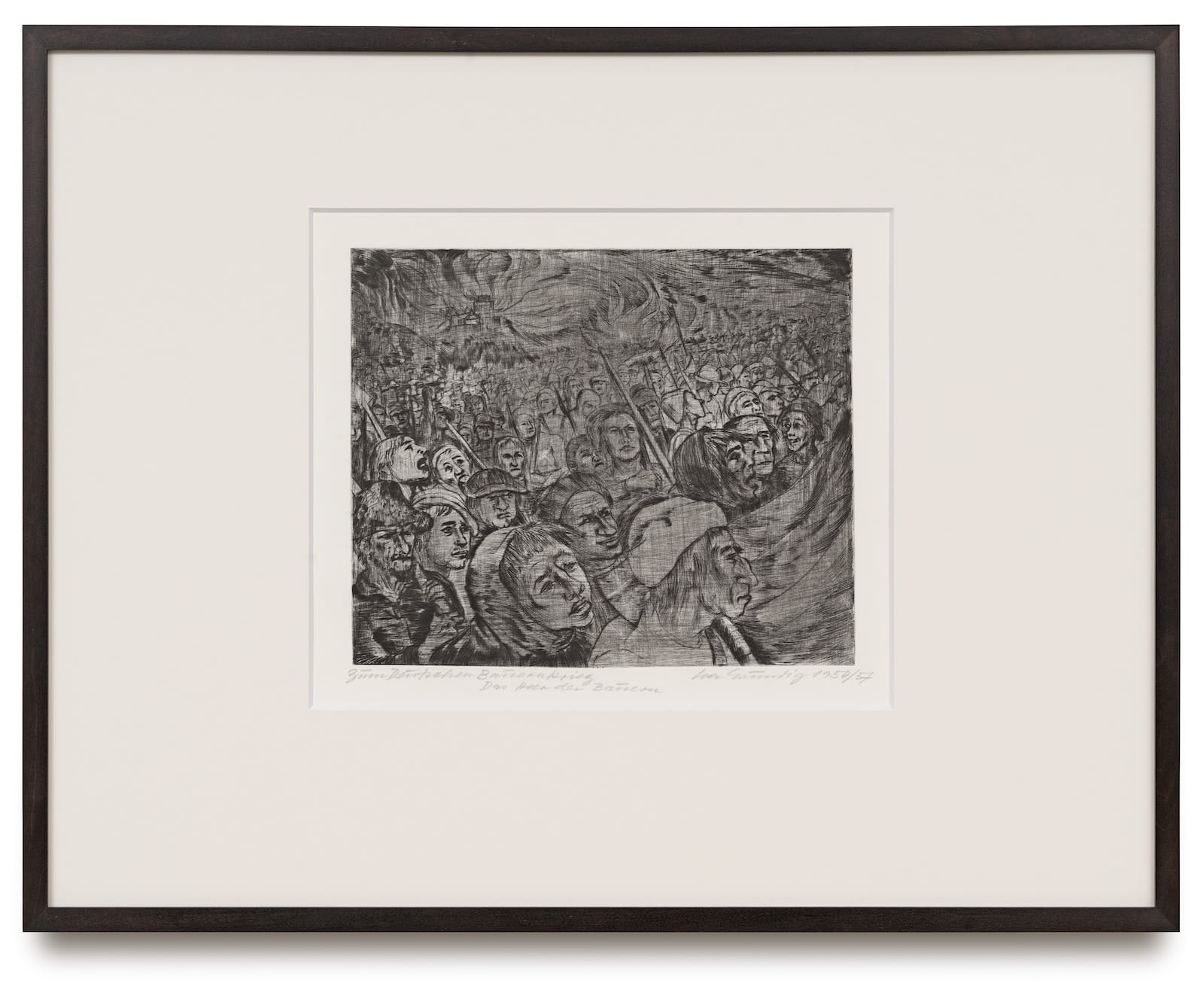

Lea Grundig

(*1906-1977, Germany)

Using the medium of Druckgrafik (print on paper) which allows for large editions at low costs, this rendering of an armed crowd stretches from the foreground to the image’s horizon. As its title reveals, what is depicted is the army of peasants from the German Peasants’ War, a historical motif that has been often deployed in national political and artistic narration. As a pre-modern uprising, Europe’s largest until the French Revolution, it was widely studied by historians and economists such as Marx and Engels. It was also referred to by the Nazis as part of a nationalistic and folkloristic narrative. Made by Grundig in 1950 and presumably reprinted in 1957, this “image of the people”—a self-conscious mass, struggling for sovereignty—aligned with the central importance the GDR gave to a Marxist reading of the historical event. Grundig was the daughter of an immigrated Jewish Ukrainian merchant, and in the resistance under the Nazis became a member of the ruling SED party, rising to high cultural and political ranks. Nevertheless, the artist, who considered herself an agitator, resisted “the smooth adaptation of the party line to the routine of real socialism,” as Eckhart Gillen described.

Bruno Serralongue

(*1968, France)

Without a press pass or official invitation, Serralongue regularly travels to the places and events where “news is happening.” As curator Pascal Beausse argues, his works “are the result of protocols which lead him to confront the concrete conditions under which information is produced and disseminated.”

In 1998, Serralongue photographed American rapper KRS-One performing at The Tibetan Freedom Concert,in Washington D.C., which was organized by Adam Yauch of the Beastie Boys to raise awareness and support for the Tibetan independence movement. Following the concert on the lawn of the Capitol building, a demonstration took place joined by members of the US Congress and Senate, representatives of the Tibetan government in exile, and personalities from the entertainment industry. Serralongue’s “image of the people” demarcates a peak in the post-Cold War order, at the much-discussed “End of History” where the triumph of liberal democracy was seen as inevitable. In the public eye, corporate, cultural activism, and NGO work eclipsed state geopolitics, and US military spending was at a historic low at the time.

In 2010, a few months after the international court in The Hague concluded that the declaration by the “representatives of the people of Kosovo” of independence did not violate the law of nations, Serralongue photographed a generic facade in the city center of Pristina. Mirroring the consolidation of state and the expansion of an economic order, logos of Western consumer brands—such as the surfing company Billabong—are mounted on the postmodernist glass architecture. As Serralongue states: “I don’t wish to answer the question of whether I am for or against independence. I acknowledge the facts: a new country has come into existence in Europe. What I find much more interesting is to envisage what this means at a time when questions of identity and immigration are constantly in the headlines.”

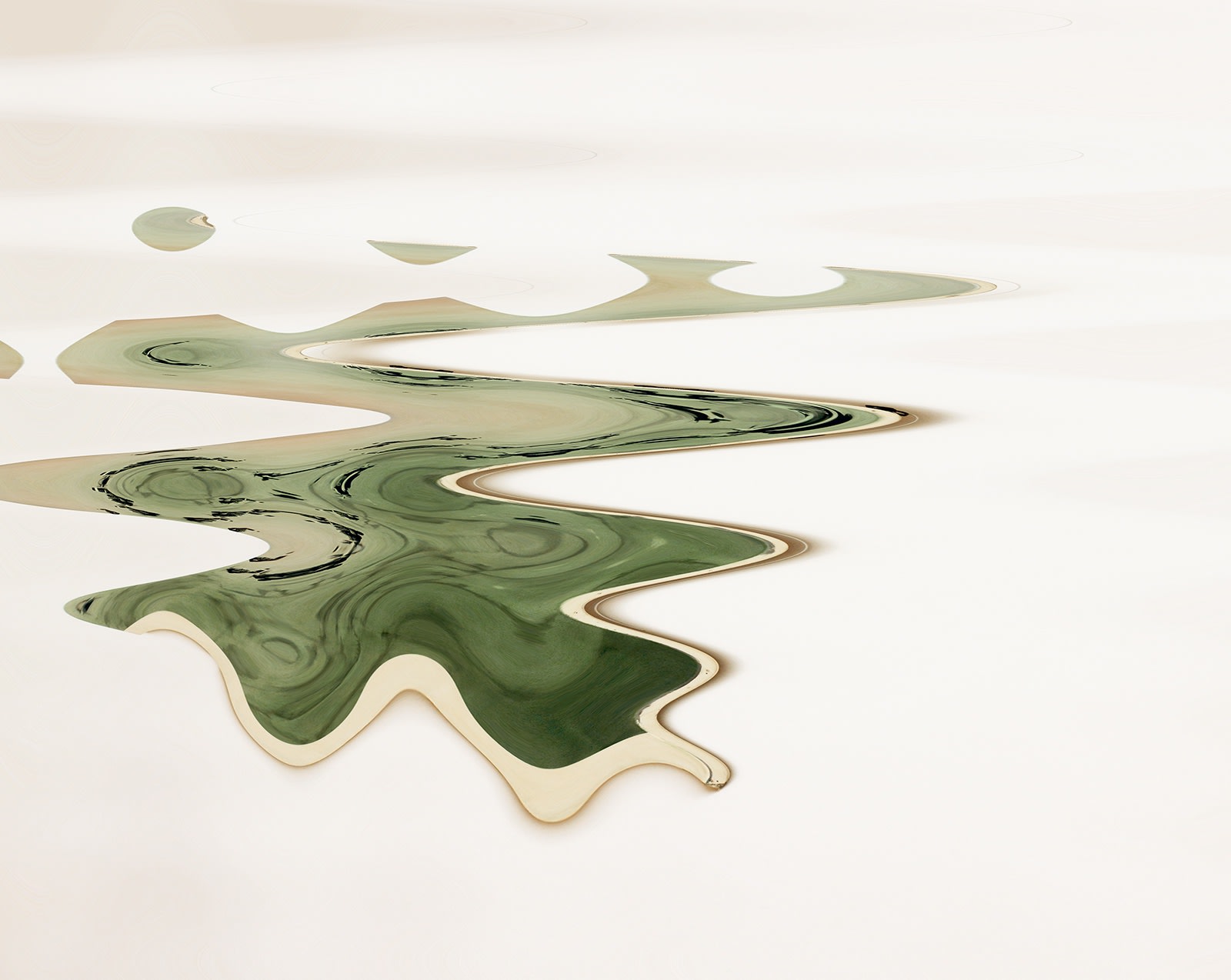

Nicolas Ceccaldi

(*1983, Canada)

Inspired by Eugène Boudin’s Impressionist depictions of cows, Ceccaldi’s strolling or resting herds are easily misread as plein air studies. Instead, they were all painted in the artist’s studio in New York of screenshots from Google Street View, and of agricultural or tourism websites from places like Normandy, Corsica, and Belgium. Playing on a postcard idea of Europe, the groups of cows appear to be in a state of oneness with their environment and become a surface for projections and interpretations. For instance, here the style could be read as alluding to the role of Impressionist painting in the construction of national and cultural identities. The very historicity and apparent generic nature of these painted cows in ornate frames are further complicated when hanging on the walls of the former “Kunst im Heim” (Art in Your Home) pavilion, a testament to the GDR’s shift in representation away from Stalinist historicism towards a “second modernism.” Against Socialist Realism, which formally tried to unite romanticism and realism and glorified the collective mastery of nature as a result of human labor, pastoralism today provokes the question of whether art can ultimately transform further to become a genuine culture for all.

Noah Barker

(*1991, USA)

Three ghostly figures coming in and out of recognition from specific perspectives and light conditions compose the Twilight Brigade. Rather than weapons, the 'brigate' bears surfboards. Their silhouettes are lifted from a poster for The Endless Summer, a film in 'search of the perfect wave'. Its recognizability and reference to post-war longing for escape made the poster a significant set design piece in Christian Petzold's Die innere Sicherheit (English release: The State I Am In) from 2000. By then, surfing had already replaced the old activities.

The individual titles hint at the protagonists of Carl Schmitt's Theory of the Partisan: Prussian general Carl von Clausewitz, author of Vom Kriege (1832), a comprehensive theory of war, Russian revolutionary Vladimir Lenin, and the Viet Cong, which through shortening to “VC” in the NATO phonetic alphabet came to be referred in US military parlance as “Charlie.”

Louise Lawler

(*1947, USA)

The artistic practice of Louise Lawler explores the “presentation of artwork and the context in which it is viewed.” In 1964 Gerhard Richter painted Mustang-Staffel (Mustang Squadron), a group of escort war planes instrumental in the Allied bombing raids over Nazi Germany that is now in the collection of the Albertinum in Dresden. At the time of the official end of the Iraq war in 2011, Lawler presented her work No Drones in London, a photograph taken of Richter’s painting from a side angle, revealing the canvas hanging system. In 2022 for the exhibition in Berlin, a digital distortion of the photograph was made (an operation that the artist calls “distorted for the times”) that is applied as a print on adhesive vinyl and adjusted to fit onto the gallery’s northwestern wall.

Oswald Oberhuber

(*1931-2020, Austria)

Oberhuber, a central figure in the Austrian post-war art scene, tirelessly advocated for a practice of “permanent change.” Marked by his early childhood in the 1930s, he later declared that he “won’t be pressed into any system ever again,” whether that system is a political one or one of artistic production, as his son Raphael Oberhuber recounts. Despite what might be understood as a deep suspicion towards institutions, Oberhuber was shaping the country’s cultural landscape not only through his art but also by his teaching, deanship at the Universität für angewandte Kunst in Vienna, and involvement in directing galleries and public commissions. His sculpture in the exhibition, made in 1952, is part of the shift in art and return to Abstraction—with the emergence of Art Informel—after the defeat of the fascist regimes in Europe. This answer to the US’ Abstract Expressionism spearheaded in Austria by Maria Lassnig, Arnulf Rainer, and Oberhuber, attempted to break away from the classical principle of form towards a new concept of image. Here Oberhuber’s sculpture that precariously balances studio-made sculpture and “found” object (eg. an actual piece of rubble) complicates the relationship between representation, abstraction, referentiality, and material.

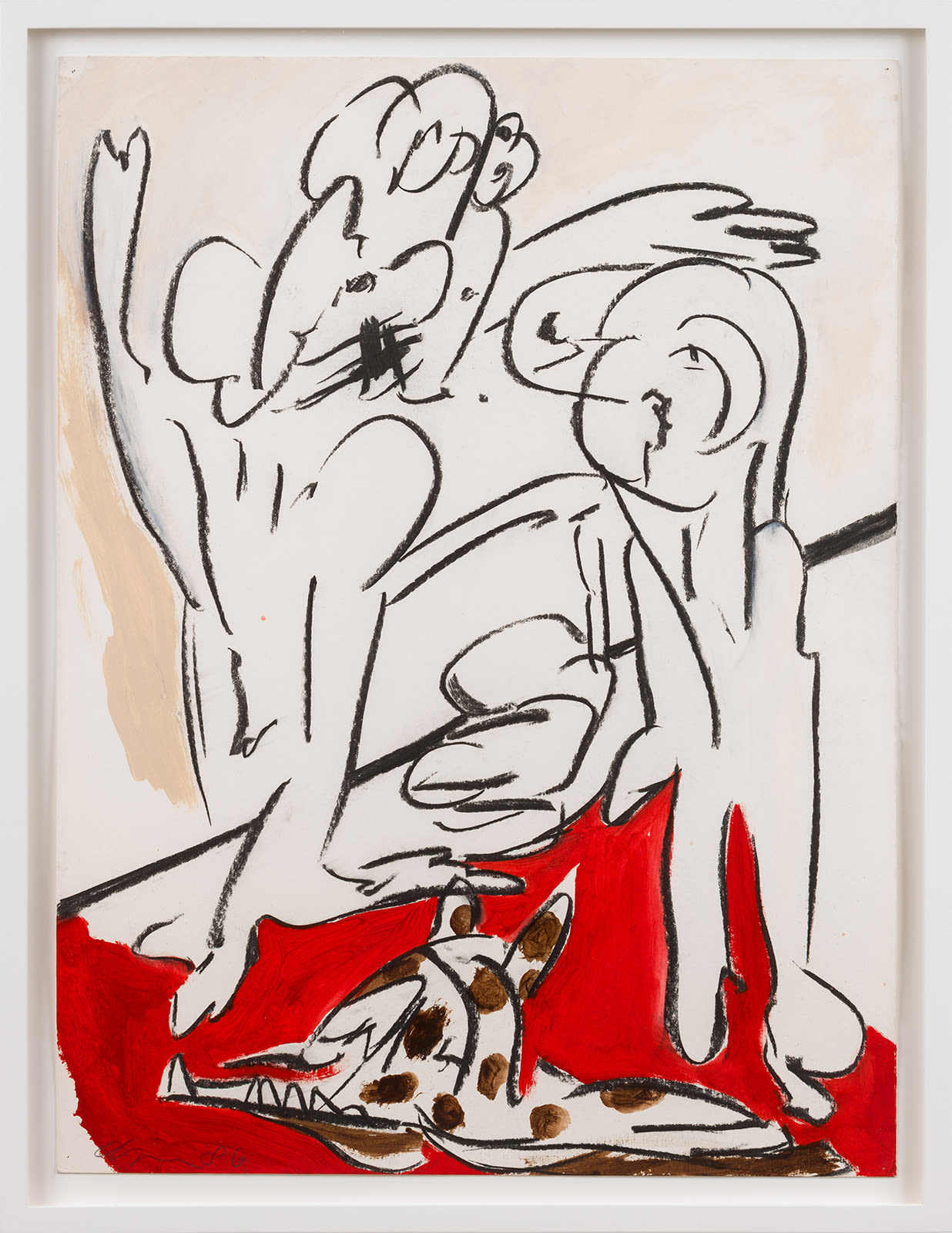

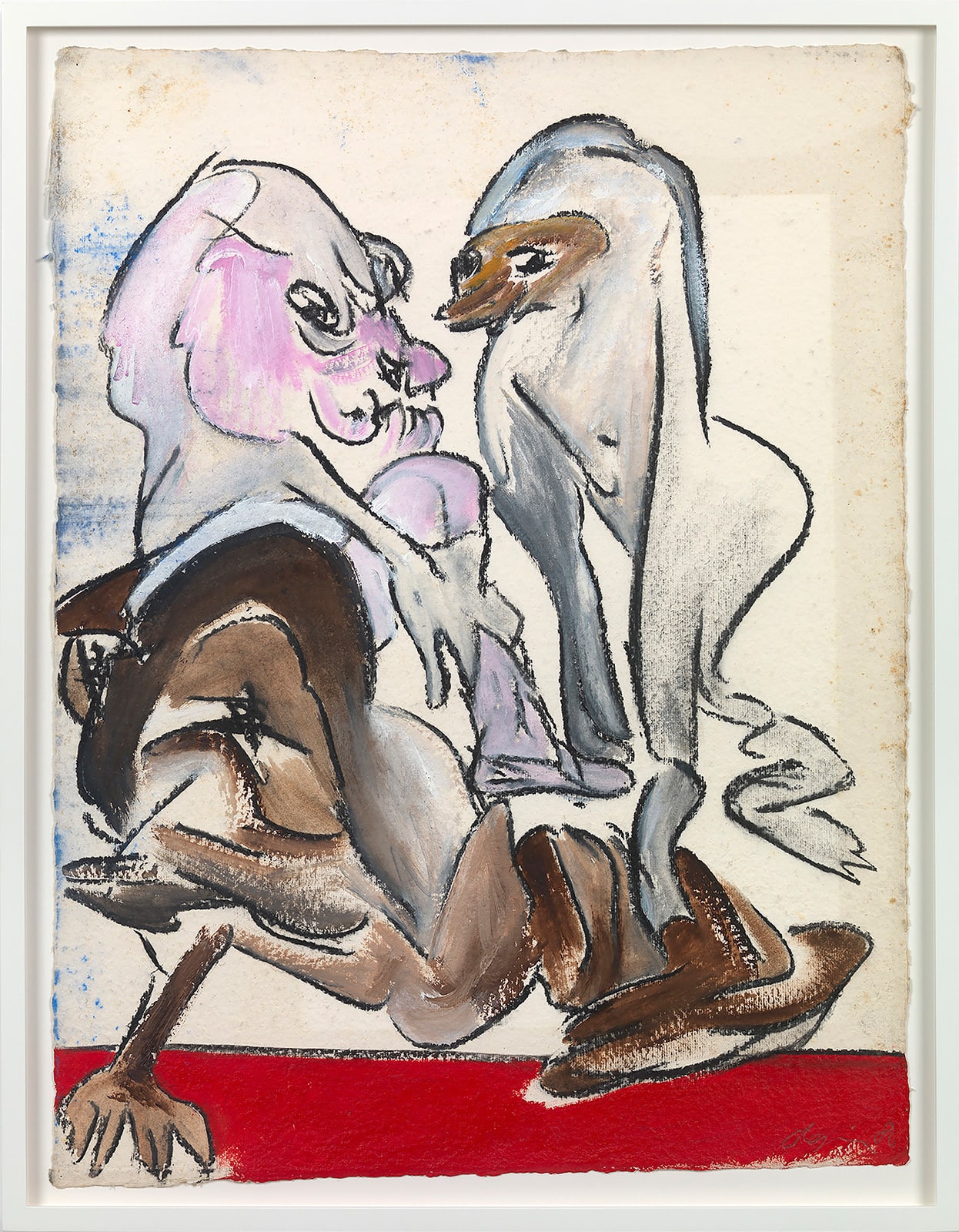

Jacqueline de Jong

(*1939, Netherlands)

De Jong, an influential figure of the post-war avant-garde in Europe and a Situationist International (SI) member, worked on a public commission in the mid-1980s. After a decade of discussions and during the time of ascending neoliberal order, Amsterdam’s new city and opera hall—The Stopera—was finally being built in an area that had been deserted after the eviction and deportation of the predominantly Jewish population during the Second World War and the Nazi occupation. This new representative place for political administration and high culture prompted fierce protest, in particular by squatters and the countercultural community, among them the Provo movement, as it was seen to drive gentrification and as part of a violent clean-up and urban renewal program. In the drawings, the groups of figures—“monsters” or “Roman punks” as she called them—occupy the public spaces of the new building and move up and down the spiral staircases in a turning motion.

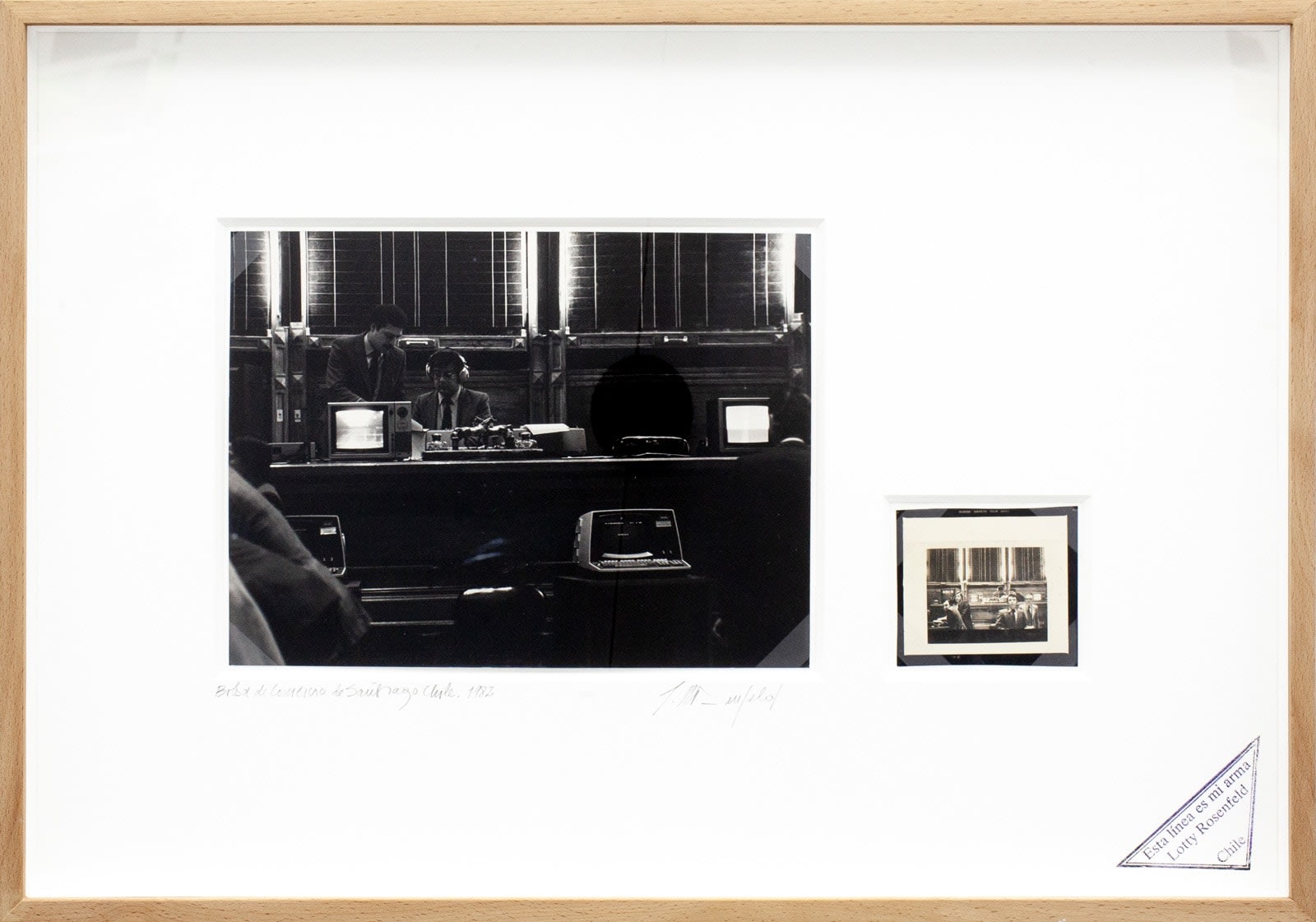

Lotty Rosenfeld

(*1943-2020, Chile)

Rosenfeld, member of the dissident artist group CADA, staged actions in public space against the authoritarianism and repression of the Pinochet regime and its neoliberal restructuring of the Chilean society. In 1979 in the capital, Santiago, Rosenfeld transformed the marking and lines of traffic lanes into crosses, creating a sign that was meant to draw attention to the relationship between communicative systems, techniques of reproduction of the social order, and the formation of compliant subjects. This action was filmed and photographed and repeated over the years at different sites of power—of political and economic significance—such as in front of the Bank of England in London. In 1982, she staged the last part of a three-part action titled Una Herida Americana (An American Wound) in the stock exchange of Santiago. On two monitors Rosenfeld was shown painting crosses on the Pan American highway in the Atacama Desert and in front of the White House in Washington D.C., hinting at the intertwinement of financial and discursive speculations with political power at the moment of the emergence of a new stage in capitalist globalization.

Peter Fend

(*1950, USA)

The video presents the artist Peter Fend speaking in front of the embassies of the newly founded Islamic Republic of Iran, the Soviet Union, and West Germany. Against the backdrop of 1979’s Washington D.C., one can hear Fend arguing for a fundamental reorganization of the world to counter ecological breakdown, war, and ethnic conflicts. Replacing nation-states with political entities based on the shape of ecological entities—saltwater basins—challenges Adam Smith’s influential economic and social theory The Wealth of Nations,which the video work’s title subverts. Contrary to Smith’s human-centered approach to production, consumption, and governance, the video outlines many of the key thoughts that inform Fend’s practice until today: use artist’s ideas to create an architecture of ecological restoration which undergirds the raison d’etre of any state, to ensure a livable environment shared by humans and non-humans in cohabitation.

Laura Langer

(*1986, Argentina)

A for Apotheke is a ubiquitous sign in today’s Germany. Langer, who is painting from a personal archive of digital photos, fuses the visual detritus of the everyday and what is of historical significance into symbolic images that attest to the state the artist, or rather we, are in. Fear, desire, longing, and identity in a waltz between personal and collective (un)conscious inform this painting on canvas that simultaneously is an image and sign. The history of the symbol of this particular A itself points to what has become an important function of the state, mediating between individual and public concerns: public health. A winning entry from a 1936 design competition for unified signage for the “gleichgeschalteten” (brought in line) German pharmacies, the slightly modified version of the A is in continued use until today.

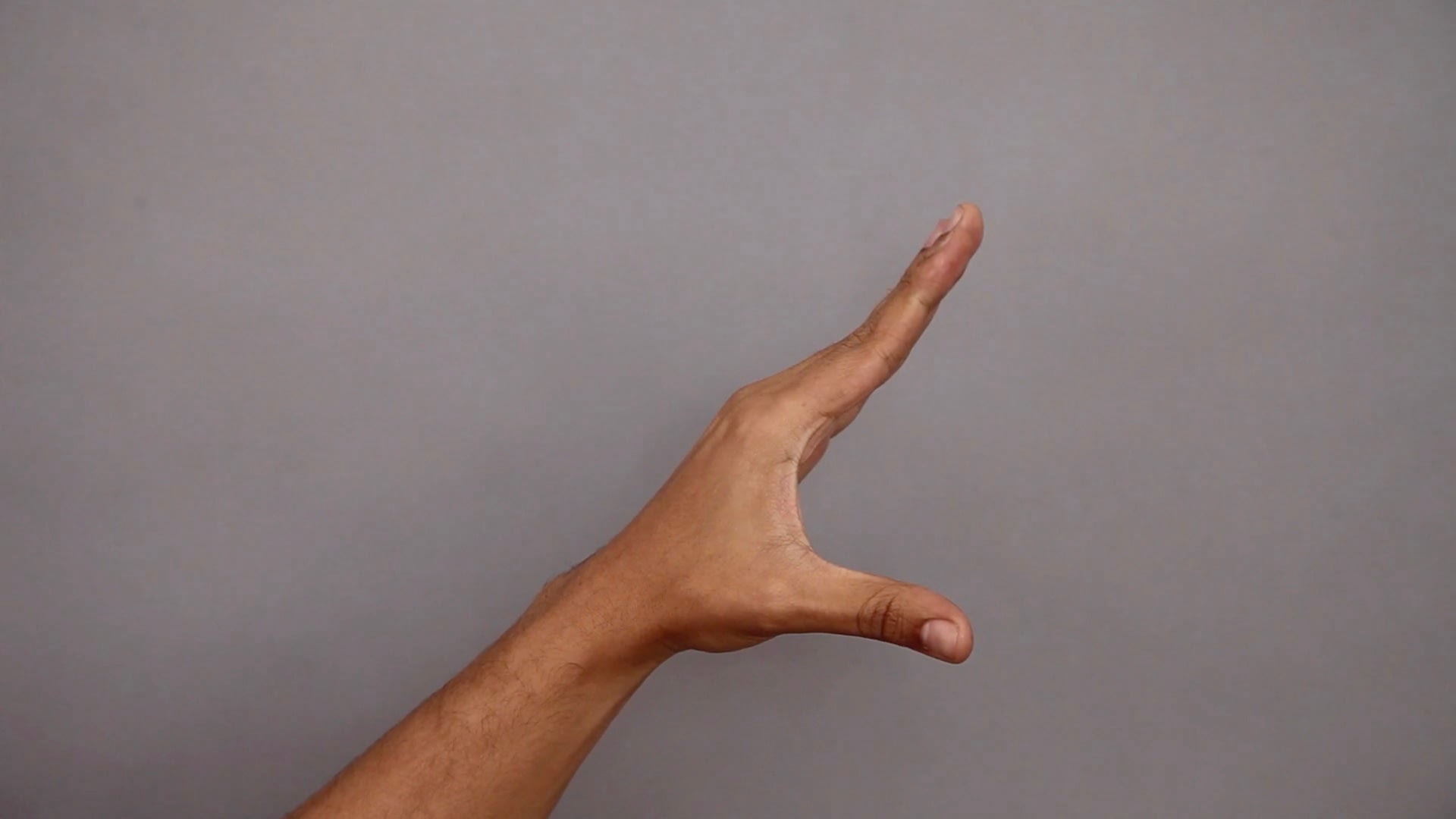

James Gregory Atkinson

(*1981, Germany)

Two clocks, positioned over the gallery’s reception counter, are set to the (North American) Central Standard and Central European Time Zones. Addressing the histories and struggles of both Afro-Germans and Black liberation in the US—Friedberg and Chicago—with personal significance for the artist, the son of an African American soldier stationed in Germany and a white German mother, also bring to mind the lasting political and cultural idea of (Trans)Atlanticism. Originating in a world divided into the two blocks of East and West, Atlanticism figures in the form of military, political, and economic institutions such as NATO, but also informs the cultural and artistic exchange and personal biographies across both sides of the Atlantic.

The video work Power Balance, which is displayed on a screen, mobilizes a stark contrast: A Black Power fist and white power salute are performed in quick succession by the artist using their own hand and voice, resembling a mantra that drives into exhaustion.

Li Ran

(*1986, China)

Facing the former monumental marching corridor of the GDR, in the video on view in the exhibition, Li Ran subverts genre when playing a Soviet Soldier off-duty wandering around in nature in a state of reminiscence and reflection. Collaged with Western classical music, pop, soundtracks from films such as the James Bond theme song, Sweet Home Alabama, Symphony No. 9, and seemingly improvised and comedic dialogues, Ran’s work appropriates the 1959 film The Fate of a Man. This original movie, which was directed by Soviet-Ukrainian Sergei Bondarchuk, recalls an image of the ideal Soviet Citizen in a narration of an individualized experience of war. It was instrumental to Moscow’s cultural diplomacy towards both the young states of Communist China and the GDR and had a lasting cultural and artistic influence on both countries. Here Ran, by pitting ideology against performativity, dissects notions of historicity vis à vis state-mediated narratives of societal progress and modernization that also play out in the realm of the aesthetic.

Leyla Yenirce

(*1992, Kurdistan)

A fast-paced flow of images edited from what was gathered online or made by the artist—images of Kurdish female fighters, activists and journalists, pixelated landscapes, animated phoenixes, and oil paintings—is sequenced to an electronic beat. In what Yenirce describes as an “image machine,” stark opposites are mobilized: rave visuals, music videos, moving-image tributes to those killed or still fighting for sovereignty and self-determination, and documentation of resistance by the underrepresented. In a moment of intensified information—or rather image warfare—where war is spectated or “consumed” via TikTok, images create cohesion, purpose, and legitimacy for particular struggles and sites of a conflict.

Bri Williams

(*1993, USA)

Composed of a fragment of a stand of a carousel horse, the sculpture is titled Stare. This term describing a hostile gaze could also allude to its ornate structure, which converges to a sharp arrowhead visually piercing the space and the viewer as they approach the work. This appropriated object, itself harnessing the premonition of violence, allegorically acts in the absence of the horse—a hardy riding, pack, and draught animal that was instrumental in warfare and colonialist expansion—as a tool for the subjugation of nature and humans alike.

-

Works

-

Laura LangerMoon Skull, 2022Acrylic and oil on canvas150 x 110 cm

Laura LangerMoon Skull, 2022Acrylic and oil on canvas150 x 110 cm

59.1 x 43.3 inches -

Nicolas CeccaldiHerd resting, 2022Oil on cardboard mounted on foamcore, artist's frameSigned and dated versoImage dimensions:

Nicolas CeccaldiHerd resting, 2022Oil on cardboard mounted on foamcore, artist's frameSigned and dated versoImage dimensions:

61 x 90.8 cm / 24 x 35.7 inches

Framed dimensions:

71.8 x 101.6 cm / 28.3 x 40 inches -

James Gregory AtkinsonPower Balance, 2012HD video, sound, loop7:37 minEdition of 3 + 2 AP

James Gregory AtkinsonPower Balance, 2012HD video, sound, loop7:37 minEdition of 3 + 2 AP -

Lea GrundigBauernkriege, 1950/57Etching, framed65 x 50 cm

Lea GrundigBauernkriege, 1950/57Etching, framed65 x 50 cm

25.6 x 19.7 inches -

Bruno SerralongueKRS ONE on Stage (Washington DC), 1998Ilfochrome Classic print (2003), mounted on aluminiumImage dimensions:

Bruno SerralongueKRS ONE on Stage (Washington DC), 1998Ilfochrome Classic print (2003), mounted on aluminiumImage dimensions:

125 x 156 cm / 49.2 x 61.4 inches

Framed dimensions:

127.5 x 158.5 cm / 50.2 x 62.2 inchesEdition of 3 plus 2 AP -

Noah BarkerTwilight Brigade (Charlie, Clausewitz, and Vladimir), 2021Gloss paintDimensions variable

Noah BarkerTwilight Brigade (Charlie, Clausewitz, and Vladimir), 2021Gloss paintDimensions variable -

Nicolas CeccaldiErrance, 2022Oil on paper mounted on canvas, artist's frameSigned and dated versoImage dimensions:

Nicolas CeccaldiErrance, 2022Oil on paper mounted on canvas, artist's frameSigned and dated versoImage dimensions:

61 x 76.2 cm / 24 x 30 inches

Framed dimensions:

66.7 x 81.9 cm / 26.2 x 32.2 inches -

![Louise Lawler No Drones (adjusted to fit, distorted for the times), 2010/2011/2022 [as adjusted for the exhibition 'the state I am in', 2022] Adhesive wall material 457.2 x 574 cm 179.9 x 226 inches Edition 1/1 + 1 AP](data:image/gif;base64,R0lGODlhAQABAIAAAAAAAP///yH5BAEAAAAALAAAAAABAAEAAAIBRAA7) Louise LawlerNo Drones (adjusted to fit, distorted for the times), 2010/2011/2022 [as adjusted for the exhibition 'the state I am in', 2022]Adhesive wall material457.2 x 574 cm

Louise LawlerNo Drones (adjusted to fit, distorted for the times), 2010/2011/2022 [as adjusted for the exhibition 'the state I am in', 2022]Adhesive wall material457.2 x 574 cm

179.9 x 226 inchesEdition 1/1 + 1 AP -

Nicolas CeccaldiBy the sea, 2022Oil and pastel on paper mounted on canvas, artist's frameSigned and dated versoImage dimensions:

Nicolas CeccaldiBy the sea, 2022Oil and pastel on paper mounted on canvas, artist's frameSigned and dated versoImage dimensions:

61 x 91.4 cm / 24 x 36 inches

Framed dimensions:

80 x 110.5 cm / 31.5 x 43.5 inches -

Oswald OberhuberUntitled, 1952Mortar, brick, round bar steelSigned and dated on the bottom224 x 28 x 18.7 cm

Oswald OberhuberUntitled, 1952Mortar, brick, round bar steelSigned and dated on the bottom224 x 28 x 18.7 cm

88.2 x 11 x 7.4 inches -

Jacqueline de JongUntitled (Upstairs-Downstairs), 1986Charcoal and acrylic on cartridge paperSigned and dated rectoImage dimensions:

Jacqueline de JongUntitled (Upstairs-Downstairs), 1986Charcoal and acrylic on cartridge paperSigned and dated rectoImage dimensions:

60 x 45 cm / 23.6 x 17.7 inches

Framed dimensions:

66 x 51 cm / 26 x 20.1 inches -

Jacqueline de JongUntitled (Upstairs-Downstairs), 1986Charcoal, crayon and acrylic on watercolour paperImage dimensions:

Jacqueline de JongUntitled (Upstairs-Downstairs), 1986Charcoal, crayon and acrylic on watercolour paperImage dimensions:

68 x 51 cm / 26.8 x 20.1 inches

Framed dimensions:

74 x 58 cm / 29.1 x 22.8 inches -

Jacqueline de JongUntitled (Upstairs-Downstairs), 1985Charcoal, crayon and acrylic on watercolour paperImage dimensions:

Jacqueline de JongUntitled (Upstairs-Downstairs), 1985Charcoal, crayon and acrylic on watercolour paperImage dimensions:

91 x 63 cm / 35.8 x 24.8 inches

Framed dimensions:

67.8 x 96.4 cm / 26.7 x 38 inches -

Lotty RosenfeldBANCO DE INGLATERRA, 1996From the series 'A Mile of Crosses on the Asphalt'

Lotty RosenfeldBANCO DE INGLATERRA, 1996From the series 'A Mile of Crosses on the Asphalt'

Two vintage b/w photographsSigned and stampedFramed dimensions:

33 x 38.5 cm / 13 x 15.5 inches -

Jacqueline de JongUntitled (Upstairs-Downstairs), 1984Charcoal, crayon and acrylic on cartridge paperImage dimensions:

Jacqueline de JongUntitled (Upstairs-Downstairs), 1984Charcoal, crayon and acrylic on cartridge paperImage dimensions:

45 x 60 cm / 17.7 x 23.6 inches

Framed dimensions:

51 x 66 cm / 20.1 x 26 inches -

Lotty RosenfeldBOLSA DE COMERCIO DE SANTIAGO, 1982From the series 'A Mile of Crosses on the Asphalt'

Lotty RosenfeldBOLSA DE COMERCIO DE SANTIAGO, 1982From the series 'A Mile of Crosses on the Asphalt'

Two vintage b/w photographs, video screenshotsSigned and stampedFramed dimensions:

36.9 x 52.8 cm / 14.53 x 20.8 inches -

![Lotty Rosenfeld UNA MILLA DE CRUCES SOBRE EL PAVIMENTO [A Mile of Crosses on the Asphalt], 1979 Video, 4:3, color, sound 5:15 min Edition of 25](data:image/gif;base64,R0lGODlhAQABAIAAAAAAAP///yH5BAEAAAAALAAAAAABAAEAAAIBRAA7) Lotty RosenfeldUNA MILLA DE CRUCES SOBRE EL PAVIMENTO [A Mile of Crosses on the Asphalt], 1979Video, 4:3, color, sound5:15 minEdition of 25

Lotty RosenfeldUNA MILLA DE CRUCES SOBRE EL PAVIMENTO [A Mile of Crosses on the Asphalt], 1979Video, 4:3, color, sound5:15 minEdition of 25 -

Peter FendWealth of Basins - Death of Nations, 1979Video

Peter FendWealth of Basins - Death of Nations, 1979Video

Filmed and directed by Robert Polidori45:31 min -

James Gregory AtkinsonCET CST, 2021/22Two Clocks32 cm / 12.6 inchesEdition of 3 + 2 AP

James Gregory AtkinsonCET CST, 2021/22Two Clocks32 cm / 12.6 inchesEdition of 3 + 2 AP -

Leyla YenirceBeing Strong is Hard, 2021Single-channel video and sound installation, color, 4:13 minDimensions variableEdition of 3 + 1 AP

Leyla YenirceBeing Strong is Hard, 2021Single-channel video and sound installation, color, 4:13 minDimensions variableEdition of 3 + 1 AP -

Bruno SerralongueDevantures, centre ville de Pristina, Kosovo, 8 novembre 2010, 2010Ilfochrome print, mounted on aluminiumImage dimensions:

Bruno SerralongueDevantures, centre ville de Pristina, Kosovo, 8 novembre 2010, 2010Ilfochrome print, mounted on aluminiumImage dimensions:

125 x 156 cm / 49.2 x 61.4 inches

Framed dimensions:

127.5 x 158.5 cm / 50.2 x 62.2 inchesEdition of 3 plus 1 AP -

Li RanFrom Truck Driver to the Political Commissar of the Mounted Troops, 2012Video8:50 min

Li RanFrom Truck Driver to the Political Commissar of the Mounted Troops, 2012Video8:50 min -

Bri WilliamsStare, 2021Carousel horse stand10.8 x 38 x 53.2 cm

Bri WilliamsStare, 2021Carousel horse stand10.8 x 38 x 53.2 cm

4.3 x 15 x 20.9 inches

-

-

Installation Views

-

Press

-

Related Artists

![Louise Lawler No Drones (adjusted to fit, distorted for the times), 2010/2011/2022 [as adjusted for the exhibition 'the state I am in', 2022] Adhesive wall material 457.2 x 574 cm 179.9 x 226 inches Edition 1/1 + 1 AP](https://artlogic-res.cloudinary.com/w_2400,h_2400,c_limit,f_auto,fl_lossy,q_auto/artlogicstorage/capitainpetzel/images/view/05dc69fd51d75f35c61b54bdd6e37390j/capitainpetzel-louise-lawler-no-drones-adjusted-to-fit-distorted-for-the-times-2010-2011-2022-as-adjusted-for-the-exhibition-the-state-i-am-in-2022.jpg)

![Lotty Rosenfeld UNA MILLA DE CRUCES SOBRE EL PAVIMENTO [A Mile of Crosses on the Asphalt], 1979 Video, 4:3, color, sound 5:15 min Edition of 25](https://artlogic-res.cloudinary.com/w_2400,h_2400,c_limit,f_auto,fl_lossy,q_auto/artlogicstorage/capitainpetzel/images/view/b751163e14a768f3efbf51f38737d2b0j/capitainpetzel-lotty-rosenfeld-una-milla-de-cruces-sobre-el-pavimento-a-mile-of-crosses-on-the-asphalt-1979.jpg)