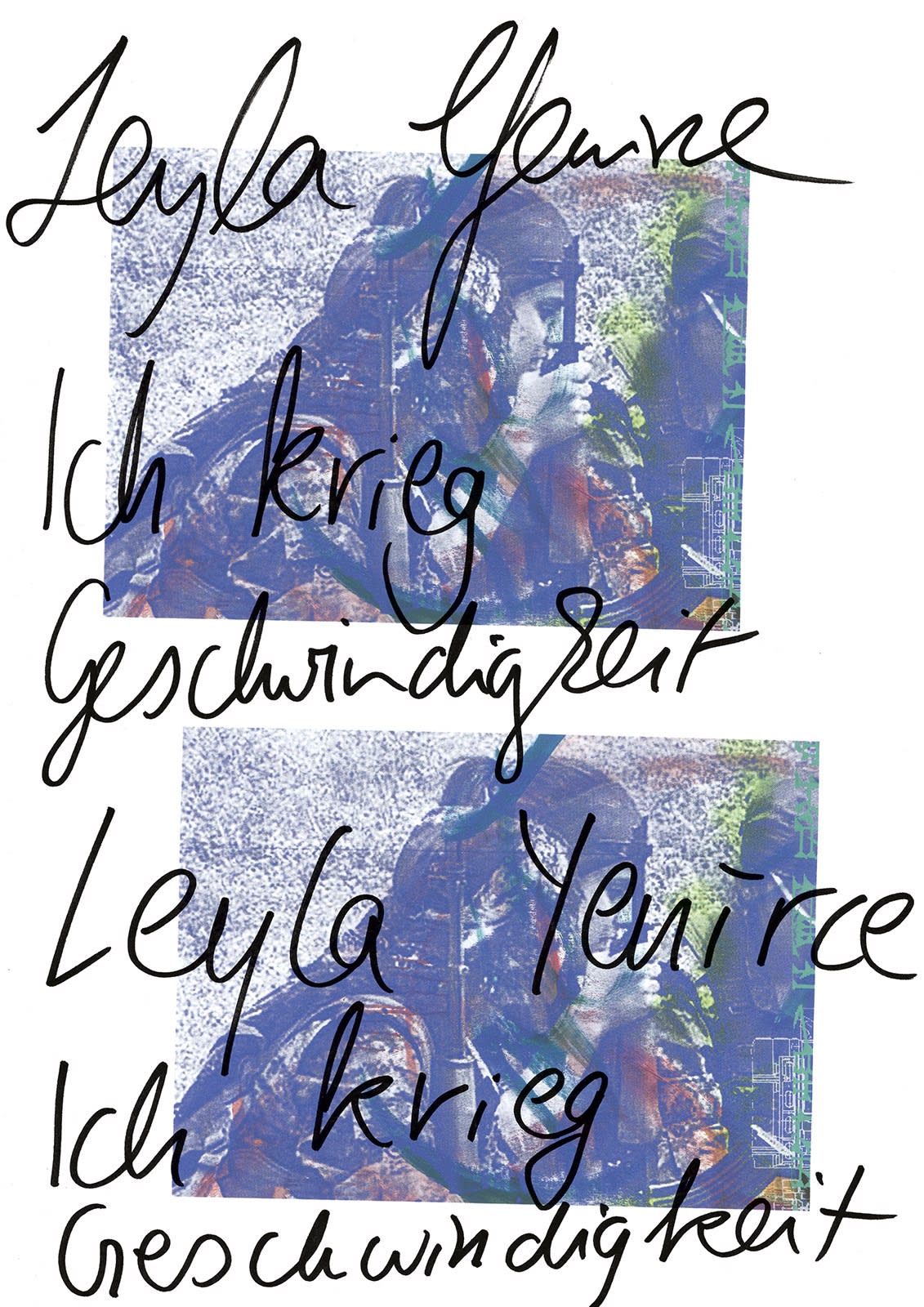

Leyla Yenirce: Ich krieg Geschwindigkeit

-

Overview

“In themselves, the pictures, the phases, the elements of the whole are innocent and indecipherable”, Sergei Eisenstein once remarked. “The blow” occurs only when the individual elements are linked together to form a sequential image and really pick up speed. Ich krieg Geschwindigkeit (I’m gaining speed), the title of Leyla Yenirce’s exhibition, resounds metaphorically through the gallery space like a slogan, not only releasing visual energies, but allowing them to flourish within the architecture of montage, alongside images yet to be created – or, as Eisenstein would say, a “third something”.

On the balcony, large-format canvases (Rhythm of the Night I-IV) are hung in a line like a cinematic sequence. They depict a grid-like succession of the same monochrome silkscreen motif. Fragments of a photograph that appears on all the canvases in the exhibition show the outlines of two people with machine guns held aloft, as if ready to resist. This is an image circulating on the web of a group of young female fighters from the Kurdish Women’s Protection Unit (YPJ) huddled together and discussing military strategies at a training camp near Qamishli, Syria. On her canvases, Yenirce appropriates, alienates, and samples this photograph almost beyond recognition, superimposing it and even sabotaging its visual impact with hastily applied, electrified strips of brightly colored oil pastels, paint, and acrylic spray – like an emotionally driven smear attack against the interpretive sovereignty of the image.

It is tempting to draw analogies between the canvases and Andy Warhol’s grainy series of silkscreen prints, Death and Disaster (1962-1968). It was with this series, begun the same year that Marilyn Monroe took her own life with an overdose of sleeping pills, that Warhol’s preoccupation with the glossy commodity aesthetics of America collided with a flourishing interest in the darker aspects of Kennedy’s “time for greatness”. Rendered in garish pastel shades or black and silver, the series captures the sesationalism of impending catastrophe and the mass media’s rabid frenzy for images – overt inspiration comes from an exploitative New York Mirror front page about a disastrous plane crash: “129 DIE IN JET!”

Yenirce also plays with the effectiveness, instrumentalization, performance, and commodification of a journalistic image. Detached from its underlying informational contexts, as well as its patterns of circulation and usage in image warfare, the image is repeatedly exposed, copied, cropped, manipulated, and even “moved” from canvas to canvas in the exhibition space as a “poor image” (Hito Steyerl). The more this “poor image” accelerates – is reproduced, in other words – the more inferior and porous it becomes, despite reaching a wider audience. It gains speed in what Yenirce calls an “image machine”, which is fed news and continuously duplicates it, before transposing its own archival conception onto the canvas.

In the main room of the gallery, this image machine continues to whirl on canvases hanging opposite each other. In these works, the frequently cited commodity aspect of painting – its vitalist potential – collides even more so with the economy of the “poor image”. This time there are only glimpses of different sections of the original photograph on the canvases. They are interrupted by copies of themselves, by construction drawings of an AK-47 machine gun, screen-printed vertical strips of color, and Sumerian cuneiform characters resembling the infamous “digital rain” of The Matrix. Here, though, they pelt across the canvas rather than the screen (Alphi-11, 2022). These “insignias” are countered by the traces left by Yenirce’s own body: jagged brushstrokes that change direction and consolidate into an excess of abstract, proliferating webs (RSKBSNSS, 2022) and indecipherable signatures (Präludium; Meine Leben, 2022). “Berxwedan Jîyane” means “resistance is life” in Kurdish. Other “pluriversal” theories of knowledge are clearly at work on the canvases, which resist the authority of a hypothetical pictorial message. Difference has an originative effect here rather than a secondary one. Opacity, too, enables rather than inhibits, facilitating the “haptic visuality” described by Laura U. Marks and promoted by Yenirce herself, even beyond the canvas. Crunching footsteps in the snow, a mystical synth melody, casual conversations, a looming, ominous rush of noise, a plaintive piano motif, devastating sobs, and spirited laughter all intertwine to form an acoustic immersion in the basement. As if the gaze is haptically stimulated by the withdrawal of representative visibility rather than in spite of it, the three-dimensional collage virtually triggers the eye to mutate into a multisensory organ – to flee, even, into escapism.

In this visceral ode, Yenirce reinterprets the Armenian-Kurdish folk singer Aram Tigran’s lyrics to the song “Peşiya Malê”. Instead of fleeing to the mountains because of a man’s love, Yenirce’s woman dedicates herself to the fight – thus chronicling the death and resurrection of Kurdish freedom fighter Helbest Jiyan, who was murdered during an airstrike by the Turkish army in 2019.

Ultimately, Yenirce’s works not only deal with resistance against the perceived hegemonic power of the image – for example, the aestheticization of the resistance of Kurdish fighters, who, through politics of remediation and “digital witnessing” (Lilie Chouliaraki), are “martyrized” both in and beyond global online media as a symbol of feminist struggle. The primary focus here is the real conditions of existence of these images in swarm circulation or dispersion: the things that are incorporated into them and those that emerge from them. This arena is not for the “representatives” of power, but for what power, in all its abstract dimensions, can produce by means of the “aesthetic of the in-between” and affective potential. This also includes initiating a changing (power) discourse as a complicit endeavor.

This kind of transformation implies a gaze that also lends visibility to unseen resistance – the “metamorphosis into the small”, as Elias Canetti says, in paraphrasing Kafka’s flawed self-defense strategy – that not only offers a bombastic riposte to authority but also empowers us to elude them. This haptic, “dispossessed” form of seeing resists the urge to identify what has happened and instead intentionally merges with it – with the empty spaces of the montage, the bare white walls in the room, the footsteps in the snow. For what has happened is not only reflected in each individual image but also in the acts of looking, which, we can hope, will also gain speed, eventually.

Text by Elisa R. Linn

Leyla Yenirce, born 1992 in Qubîn, Kurdistan, is currently based in Berlin, Germany. Having graduated from the Hamburg University of Fine Arts, her first solo exhibition SO MUCH ENERGY took place at the Kunsthaus Hamburg in 2022. In 2024, Yenirce's video work Being Stong is Hard was screened at the International Film Festival Rotterdam. The artist will also participate in group exhibitions at Museum Folkwang, Essen. Among other notable institutions, Yenirce has exhibited at the Kunsthalle Münster (2024); Haus der Kunst, Munich (2023); Galerie für Zeitgenössische Kunst, Leipzig (2023) and Halle für Kunst Lueneburg (2022). Yenirce is one of the recipients of the 2024 Kunstpreis Berlin and 2022 ars viva Prize. In addition to numerous other scholarships and prizes, including Federal Prize for Art Students, Bonn (2021), the Playground Art Prize, Nuremberg (2021) and the Hamburg Music Prize (2019), Yenirce has been part of various group exhibitions, including Video Digest #1, Moltkerei, Cologne (2023), Gallery Weekend Festival, Studio Mondial, Berlin (2023), Kein Schlussstrich Festival, Kampnagel, Hamburg (2021), Paradise, Kurdish Film Festival, Berlin (2020) and Hi Ventilation, Kunstverein Harburger Bahnhof, Hamburg (2019).

Her work is held in the permanent collection of the Mudam, Luxembourg, Detroit Institute of Arts Museum and Kistefos Museum, Norway.

-

-

Installation Views